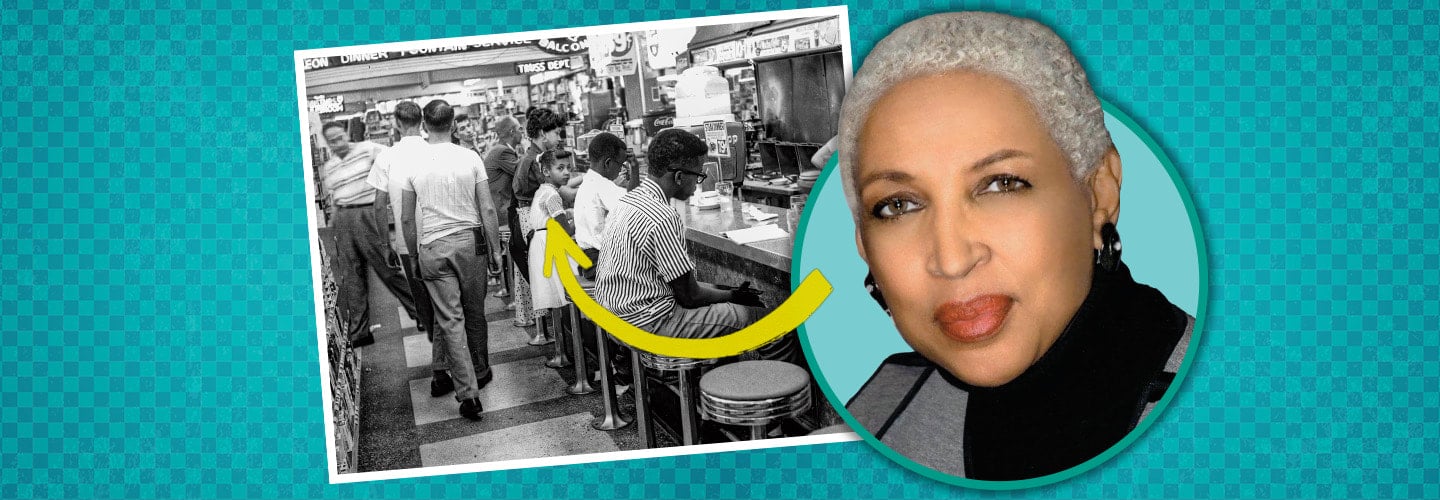

Courtesy of Ayanna Najuma

Ayanna Najuma

On a hot August day in 1958, Ayanna Najuma walked into the Katz Drug Store in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The 7-year-old and 12 other kids sat down at the lunch counter. They tried to order food, but the waitresses ignored them. The kids sat for hours. No one would serve the students for one reason. They were Black.

The restaurant was one of many in the city that refused to serve Black people at the time. But Ayanna and the other kids weren’t there to eat. They wanted to end segregation. That’s the forced separation of people based on race. The kids, who ranged in age from 6 to 17, were holding a type of protest called a sit-in.

“We said to each other, ‘We want a change. Why wait? Let’s do it now,’” Ayanna recalls.

It was a hot August day in 1958. Ayanna Najuma walked into the Katz Drug Store in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The 7-year-old was with 12 other kids. They sat down at the lunch counter and tried to order food. But the waitresses ignored them. The kids sat for hours. No one would serve them. Why? Because they were Black.

Many restaurants in the city refused to serve Black people at the time. Katz Drug Store was one of them. But Ayanna and the other kids weren’t there to eat. They wanted to end segregation. That’s the forced separation of people based on race. The kids ranged in age from 6 to 17. They were holding a type of protest called a sit-in.

“We said to each other, ‘We want a change. Why wait? Let’s do it now,’” Ayanna recalls.