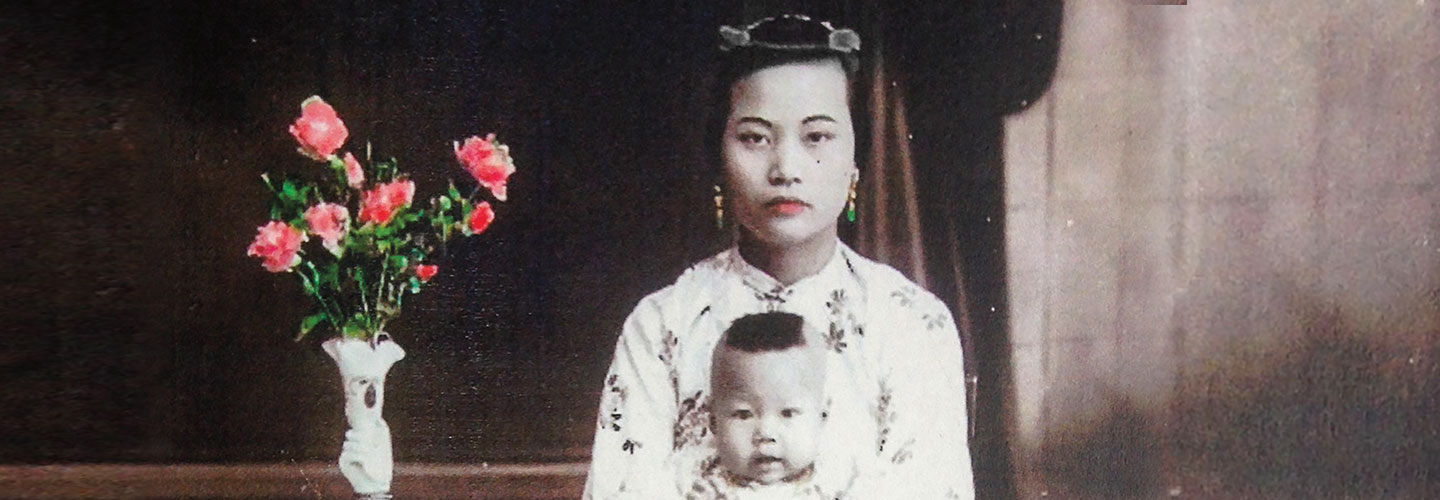

courtesty of Calvin Ong

Calving Ong today

Imagine leaving your family and friends and moving to a new country. You don’t speak the language and you know almost no one there. To get to your new home, you’ll spend 18 days at sea, on a ship crowded with strangers.

That’s exactly what 10-year-old Calvin Ong did in 1937, when he boarded a ship from China, all alone. He was headed to California to start a new life with his father, who had moved there before Ong was born.

“America was a land of opportunity,” Ong, now 93, says.

But he soon found out that the American dream would not come easily. Ong’s first stop in the U.S. was Angel Island, near San Francisco. The immigration station there was built to keep Asian immigrants out of America, not welcome them.